- The World Bank Group [Online]. (2024): https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?end=1972&locations=1W-US&start=1960&view=chart.

- H.R.4444 - 106th Congress (1999-2000): To authorize extension of nondiscriminatory treatment (normal trade relations treatment) to the People's Republic of China, and to establish a framework for relations between the United States and the People's Republic of China. (2000, octobre 10). https://www.congress.gov/bill/106th-congress/house-bill/4444

- Lippit, V. D., Baiman, R., Kotz, D., Larudee, M., Li, M., Lippit, V., & Osterreich, S. (2011). Introduction: China’s Rise in the Global Economy. Review of Radical Political Economics, 43(1), 5-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0486613410385445

- H.R.4346 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): CHIPS and Science Act. (2022, août 9). https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/4346

- Alonso Bernal Cameron Carter, Ishpreet Singh, Kathy Cao, Olivia Madreperla John Hopkins University, NATO – OTAN / JOHNS HOPKINS University. (2020), FALL 2020 COGNITIVE WARFARE. An attack on truth and thought report.

- Israel Public Policy Institute. Disinformation in the Digital Public Sphere (2024). https://www.ippi.org.il/fellowship/disinformation/

- Idem.

- IRES. (Octobre 2020), Etude "Réseaux sociaux au Maroc : enjeux et perspectives".

- Thales Group. (2024), article “ Collaborative Combat | Thales Group ’’ Consulté le 1er octobre 2024 à partir de : Collaborative Combat | Thales Group.

- Kiser, A., Hess, J., Bouhafa, E. M., & Williams, S. (2017), The combat cloud: enabling multi-domain command and control across the range of military operations. Air Command and Staff College: https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/AUPress/Papers/wf_0065_hess_combat_cloud.pdf

- Margaux Bourgasser, F. A. (2022). Le COMBAT COLLABORATIF, COMBAT du FUTUR ? Consulté le 04 23, 2024, sur : https://www.defense.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/ministere-armees/esprit-defense-numero-5-automne-2022-dossier-combat-collaboratif-combat-du-futur.pdf

- "Liaison 16" permet aux Rafales 4 de communiquer avec différents corps de l’armée dans le champ de bataille. Programme qui lie l’armée de l’air et l’armée de terre française. "Conect@Aero" permet la connectivité des acteurs de l’armée de l’air française. "Axon@V" permet la connectivité des acteurs de la marine nationale française.

- Thales. (2024) The Land Tactical Collaborative Combat (LATACC) project accelerates the introduction of collaborative combat by European coalition forces. Consulted on October 9, 2024. https://www.thalesgroup.com/en/worldwide/defence/press_release/land-tactical-collaborative-combat-latacc-project-accelerates

- Bulletin Officiel Dahir n° 1-20-70 du 4 hija 1441 (25 juillet 2020) portant promulgation de la loi n° 10-20 relative aux matériels et équipements de défense et de sécurité, aux armes et aux munitions. [Online].

- Nations Unies. Conférence des Nations Unies. L’environnement et le développement, du 9 juin au 14 juin 1992 | Rio de Janeiro.

- ISO 26000. (2024), article “how to contribute to sustainable development’’ https://iso26000.info/.

- Pacte Mondial- Réseau France. (2024), article “Le Pacte mondial des Nations Unies, une initiative unique pour accompagner la transformation durable des entreprises’’. Consulté le 02 octobre 2024 :Pacte mondial des Nations Unies & pacte mondial ONU

- Extrait du Message de Sa Majesté Le Roi à la troisième édition des Intégrales de l’investissement ; Royaume du Maroc, 2005 : "La responsabilité sociale des investisseurs a pour pendant et pour condition la responsabilité sociale des entreprises. À cet égard, nous suivons avec intérêt et satisfaction l’action des entreprises marocaines qui se sont volontairement engagées dans cette voie"

- Charte de la CGEM Responsabilité Sociétale des Entreprises.

- Confédération Générale des Entreprises du Maroc (CGEM). (2024), Article de la commission RSE et diversité "La CGEM réitère son engagement vis à vis de la promotion de la RSE, notamment auprès des PME". Consulté le 02 Octobre 2024.

- LUIGGI, J (2016). Cyberguerre, nouveau visage de la guerre ? Stratégique, 2016/2 N° 112. pp. 91-100. https://doi.org/10.3917/strat.112.0091.

- Intranet du Département de la Défense des Etats-Unis.

- Clifford Stoll. 1988. Stalking the wily hacker. Commun. ACM 31, 5 (May 1988), 484–497. https://doi.org/10.1145/42411.42412.

- World Economic Forum. Forum Institutional. (2024), article “2023 was a big year for cybercrime – here’s how we can make our systems safer’’ Consulted on October 1, 2024. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/01/cybersecurity-cybercrime-system-safety/.

- The European Parliament. (2023), Workshop Requested by the SEDE subcommittee “The role of cyber in the Russian war against Ukraine: Its impact and the consequences for the future of armed conflict’’. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2023/702594/EXPO_BRI(2023)702594_EN.pdf.

- NATO. Defense Education Enhancement Programme (2024), (DEEP) MEDIA – (DIS)INFORMATION – SECURITY 02, 15,2024.

- World Bank. 2019. Global Cybersecurity Capacity Program. © World Bank.

- GITEX Africa. (2023), Press release “Trend Micro's 2023 Cybersecurity Report: Safeguarding Morocco's Digital Frontiers with Detection of 52 million Threats’’

- Direction Générale de la Sécurité des Systèmes d'Information. Stratégie Nationale de Cybersécurité 2030. Juillet 2024.

- Ces données peuvent inclure des informations telles que les noms, les adresses, les numéros de téléphone, les coordonnées bancaires et transactions financières, les historiques de navigation, ….

- Nations Unies- Droits de l’Homme ; Haut-commissariat. Article “Le HCDH et le droit à la vie privée à l’ère du numérique | OHCHR’’ Consulté le 02 octobre 2024.

- Cyber Management School. (2024), article “Que se cache-t-il derrière le scandale Cambridge Analytica ?’’ Consulté le 02 octobre 2024 sur : https://www.cyber-management-school.com/ecole/les-fondamentaux-de-la-cybersecurite/quest-ce-que-le-scandale-cambridge-analytica/

- Cyber Management School. (2024), article “Qu’est ce que le logiciel Pegasus ?’’. Consulté le 02 octobre 2024 sur : https://www.cyber-management-school.com/outils-logiciels-et-technologies/quest-ce-que-le-logiciel-pegasus/

- La Commission Nationale de contrôle de la protection des Données à caractère Personnel (CNDP).

- Idem.

- Qiang, Christine Zhenwei; Liu, Yan; Steenbergen, Victor. 2021. An Investment Perspective on Global Value Chains. © Washington, DC: World Bank. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/35526 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- Eurostat. Statistics explained. (2024) "Structure of multinational enterprise groups in the EU". Consulté le 08 octobre 2024 : https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Structure_of_multinational_enterprise_groups_in_the_EU

- The World Bank Group [Online]. - 02 14, 2024. – https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=PT

- Cohen, S. D. (2007). Multinational corporations and foreign direct investment: avoiding simplicity, embracing complexity. Oxford University Press. ISBN : 139780195179354.

- OECD (2010), OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Morocco 2010, OECD Investment Policy Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264079618-en.

- Pour Acharya, la ‘capacité d’interaction’ est l’indicateur primaire qui permet de mesurer le monde multiplexe. Elle se définit comme le stock et l’intensité d’accords ou de traités qu’un pays à avec le reste du monde.

- Acharya, A., Estevadeordal, A., & Goodman, L. W. (2023). Multipolar or multiplex? Interaction capacity, global cooperation and world order. International Affairs, 99(6), 2339-2365. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiad242.

- IRES (2019). Rapport sur les Relations Internationales du Royaume / Chapitre IV- le Maroc et le Continent Africain. https://www.ires.ma/iip/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/RS-Relations-internationales-ACTUALISE-9-8-2019-Chapitre-4.pdf

- International Institute for Strategic Studies. (2024), article “The Military Balance 2024 spotlights an era of global insecurity’’ consulted online on October 02, 2024: https://www.iiss.org/press/2024/02/the-military-balance-2024-press-release/.

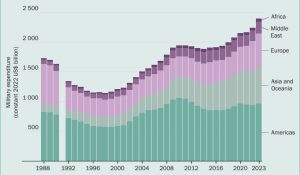

- Nan. T., Diego L., Xiao L., Lorenzo S. (2024), Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2023. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). https://doi.org/10.55163/BQGA2180

- RAND. (2024), article “Germany's New Plans for Transforming Its Defence and Foreign Policy Are Bold., They Are Also Running Into Familiar Problems’’ consulted online on October 02, 2024 : Germany's New Plans for Transforming Its Defence and Foreign Policy Are Bold. They Are Also Running Into Familiar Problems | RAND

- Institut des hautes études de défense nationale. (2023), article sur “Economie de guerre: comment la france s'adape à la haute intensité’’. Consulté le 02 Octobre 2024 Économie de guerre : comment la France s'adapte à la haute intensité ? - L'IHEDN : Institut des hautes études de défense nationale

- Paul Jones. The Center for European Policy Analysis. (2023), article “Poland Becomes a Defense Colossus ’’ Consulté le 02 octobre 2024 : Poland Becomes a Defense Colossus - CEPA.

- International Institute for Stragegic Studies. (2024), Military blog, article “Asian defence spending ambitions outstrip growth’’ Consulté le 02 octobre 2024 : Asian defence spending ambitions outstrip growth (iiss.org)

- Idem.