- Office of Educational Improvement Cognitive. Medical College of Wisconsin. (2022), "Load Theory A Guide to Applying Cognitive Load Theory to Your Teaching". https://www.mcw.edu/-/media/MCW/Education/Academic-Affairs/OEI/Faculty-Quick-Guides/Cognitive-Load-Theory.pdf

- Maitre, J-P. (2020), "La théorie de la charge cognitive". Centre de soutien à l'enseignement, Université de Lausanne. 20CSE_IN_A_NUTSHELL_01_la_theorie_de_la_charge_cognitive.pdf (unil.ch)

- Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological review, 63(2), 81. https://img3.reoveme.com/m/049764c53e25268b.pdf

- Rouet, J-F. (2001). Cognition et Technologie d'Apprentissage. Actes de la conférence Hypermédias et Apprentissage. https://tecfaetu.unige.ch/staf/staf-k/benetos/staf13/per5/glos_vs17/surcharge.htm

- Bocquillon, M., Gauthier, C., Bissonnette, S. et Derobertmasure, A. (2020). Enseignement explicite et développement de compétences : antinomie ou nécessité ? Formation et profession, 28(2), 3-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.18162/fp.2020.513

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé, (04.04.2023), Communiqué de presse. Consulté le 1er octobre 2024, à partir de : https://www.who.int/fr/news/item/04-04-2023-1-in-6-people-globally-affected-by-infertility .

- Kortenkamp, A., Scholze, M., Ermler, S., Priskorn, L., Jørgensen, N., Andersson, A. M., & Frederiksen, H. (2022). Combined exposures to bisphenols, polychlorinated dioxins, paracetamol, and phthalates as drivers of deteriorating semen quality. Environment International, 165, 107322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107322.

- Société canadienne du Cancer. (Octobre, 2020), Article sur les troubles de fertilité, Consulté le 1er octobre 2024, à partir de : https://cancer.ca/fr/treatments/side-effects/fertility-problems.

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé, (15 Septembre, 2020). Article sur l’Infertilité, Consulté le 1er octobre 2024. https://www.who.int/fr/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infertility

- Frikh, M., Benaissa, M., Kasouati, J., Benlahlou, Y., Chokairi, O., Barkiyou, M., Chadli, M., Maleb, A., & Elouennass, M. (2021). Prévalence de l´infertilité masculine dans un hôpital universitaire au Maroc [Prevalence of male infertility in a university hospital in Morocco]. The Pan African medical journal, 38, 46. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2021.38.46.19633.

- Ministère de la Santé (Maroc). (2016), Prise en charge de l'infertilité du couple. Guide pratique. https://www.sante.gov.ma/Publications/Guides-Manuels/Documents/2023/Guide%20Infertilit%C3%A9%20.pdf

- Plan Santé 2025, Bilan d’étape mai 2018 - mai 2019. (10 juin 2019), Ministère de la Santé au Maroc, Consulté le 1er octobre 2024 à partir de : https://www.sante.gov.ma/Documents/2019/06/Bilan%20d%E2%80%99%C3%A9tape%20DELM.pdf

- Nations Unies. (2023), Rapport mondial sur les drogues : Principaux points d’intérêt. https://www.unodc.org/res/WDR-2023/WDR23_SPI_French.pdf.

- Adroit Market Research. (2021), Communiqué de Presse : MEDICAL CANNABIS MARKET. Consulté le 1er octobre 2024 à partir de : https://www.adroitmarketresearch.com/press-release/medical-cannabis-market

- Nations Unies. (Juin 2022), Rapport Mondial sur les drogues : drogues et environnement. https://www.unodc.org/res/wdr2022/MS/WDR22_Booklet_5_french.pdf, page 27.

- Afsahi, K. (2017). Maroc : quand la Khardala et les hybrides bouleversent le Rif. SWAPS Géopolitique et Drogues, (87), 21-25. (Hal-01616410).

- Organe International de Contrôle des Stupéfiants. (2022), Rapport mondial sur les drogues pour 2022. ISBN: 978-92-1-001490-8, ISSN: 0257-3725. https://unis.unvienna.org/unis/uploads/documents/2023INCB/INCB_annual_report-French.pdf

- L’Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA). (11 mars 2024), Culture licite du cannabis : la Beldia marocaine entame sa Reconquista. Consulté le 1er octobre 2024 à partir de : https://www.inra.org.ma/fr/content/11032024-culture-licite-du-cannabis-la-beldia-marocaine-entame-sa-reconquista

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. (2014), Who Global Disability Action Plan 2014-2021. Consulté le 1er octobre 2024 à partir de : https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/199544/9789241509619_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- Réseau des ergothérapeutes en France. Définition de l’ergothérapie. Consulté le 1er octobre 2024 à partir de : https://www.ergotherapeutes.net/ergotherapie/

- Dominique Bilde, Sophie Montel, (25.06.2015). Article 130 du règlement. Question parlementaire (Parlement européen) avec demande de réponse écrite E-010347/15 à la Commission, Consulté le 1er octobre 2024, à partir de : https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-8-2015-010347_FR.html

- Mordor Intelligence Research & Advisory, (Janvier 2024). Analyse de la taille et de la part du marché des paris sportifs en ligne – Tendances de croissance et prévisions (2024-2029). Mordor Intelligence. Consulté le 1er octobre 2024, à partir de : https://www.mordorintelligence.com/fr/industry-reports/online-sports-betting-market

- Rapport annuel du Conseil Economique, Social et Environnemental (2021), page 126

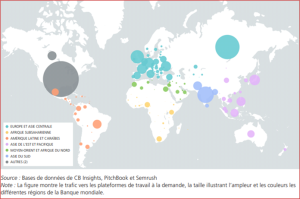

- Datta, Namita ; Rong, Chen; Singh, Sunamika; Stinshoff, Clara; Iacob, Nadina; Nigatu, Natnael Simachew; Nxumalo, Mpumelelo; Klimaviciute, Luka. (2023), Rapport d’Etudes. Working Without Borders: The Promise and Peril of Online Gig Work. WORLD BANK GROUP: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/40066.

- Idem.

- PAYONEER (2020). Rapport "Freelancing in 2020: An Abundance of Opportunities".

- Datta, Namita; Rong, Chen; Singh, Sunamika; Stinshoff, Clara; Iacob, Nadina; Nigatu, Natnael Simachew; Nxumalo, Mpumelelo; Klimaviciute, Luka. (2023). Working Without Borders: The Promise and Peril of Online Gig Work. © Washington, DC: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/40066

- Haut-Commissariat au Plan (12.08.2022). Note d’information à l’occasion de la journée Internationale de la jeunesse du 12 Aout 2022.

- Sfetcu, Nicolae. (2015). Pseudoştiinţă ? Dincolo de noi… Lulu.com. ISBN: 9781312885899.

- Tremblay, M. S., Aubert, S., Barnes, J. D., Saunders, T. J., Carson, V., Latimer-Cheung, A. E., ... & Chinapaw, M. J. (2017). Sedentary behavior research network (SBRN)–terminology consensus project process and outcome. International journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity, 14, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0525-8.

- Thivel D, Tremblay A, Genin PM, Panahi S, Rivière D and Duclos M (2018) Physical Activity, Inactivity, and Sedentary Behaviors: Definitions and Implications in Occupational Health. Front. Public Health 6: 288. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00288

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé, Région Méditerranée Orientale. (2024), Communiqué de Presse (2024). Consulté le 1er octobre 2024 à partir de : https://www.emro.who.int/fr/noncommunicable-diseases/causes/physical-inactivity.html.

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé, Région Méditerranée Orientale. (2024), Promotion de la santé et éducation sanitaire : L'activité physique. Consulté le 1er octobre 2024 à partir de : https://www.emro.who.int/health-education/physical-activity/background.html

- Saunders, T. J., McIsaac, T., Douillette, K., Gaulton, N., Hunter, S., Rhodes, R. E., ... & Healy, G. N. (2020). Sedentary behaviour and health in adults: an overview of systematic reviews. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 45(10), S197-S217.https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2020-0272

- Ministère de la Santé. (2018), Rapport de l’Enquête nationale sur les facteurs de risque communs des maladie non transmissibles, STEPS, 2017-2018.

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. (2020), Lignes directrices de l’OMS sur l’activité physique et la sédentarité : en un coup d’œil. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/337003/9789240014862-fre.pdf.

- RHPERFORMANCES. (2023), article “ Qu'est ce que l'Upskilling, Reskilling & Cross-skilling ? ’’ Consulté le 21-05-2024 à partir de : https://www.rhperformances.fr/conseil-rh/formation/upskilling/

- World Economic Forum. (2024), article “The 2020s will be a decade of upskilling. Employers should take notice”. Consulté le 1er octobre 2024 à partir de : https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/01/the-2020s-will-be-a-decade-of-upskilling-employers-should-take-notice/

- World Economic Forum. (2024), article “Reskilling revolution: preparing 1 billion people for tomorrow’s economy”. Consulté le 1er octobre 2024 à partir de : https://www.weforum.org/impact/reskilling-revolution-reaching-600-million-people-by-20

- World Economic Forum in collaboration with PwC. (2021), “Upskilling for Shared Prosperity’’ Insight Report 2021.

- The World Bank. (2024), “The world bank in Georgia’’. Overview. Country context. Last Updated: 09/04/2024. Consulted on October 1, 2024:https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/georgia/overview

- ACCELERATORS NETWORK. (2024), article “GEORGIA SKILLS ACCELERATOR”. Consulted on 05-23-2024. https://initiatives.weforum.org/georgia-skills-accelerator/home